Where do Ants Sleep at Night is a powerful, beautifully crafted 21 minute film by Dean Wei, in collaboration with choreographer Zi Wei. Like Pangäa, Stanleyville, and a few other films I’ve seen recently, Ants expresses the alienation and dehumanizing effects of modern, corporate office work. Interestingly, all of these films use the same visual symbol: an office worker who looks up from his work and gazes out the window at a bird, feeling envious of the bird’s freedom and mobility. Because Ants is set in China, the workers here are not only subject to the dehumanization and conformity which corporate workers experience in the West, but also the more encompassing conformity of China’s totalitarian system. Dean Wei, born and raised in Germany, but making films in China, has the perspective of a person raised in a society with individualist values, but now observing life in a more conformist, restrictive culture. As a dance film, Ants tells this story through movement and music, seamlessly integrating sophisticated editing and camerawork with powerful choreography to express the workers’ alienation in viscerally physical terms.

A restless, regular tapping, first heard in the music and seen in close-ups of tapping fingers, indicates the impatience of the workers, their desire for the workday to be over. Choreographer Zi Wei deftly incorporates naturalistic, everyday movement, such as workers leaving the office building en masse after work, precisely assembling them into spectacles of mass conformity. Seeing the crowd of people all walking through the building, going in and out of elevators and through doorways, all on the beat of the music, emphasizes their situation as helpless cogs in a mechanized enterprise. The inner chaos they feel, their suppressed desires, are also suggested, as they sway in unison, while riding the elevator.

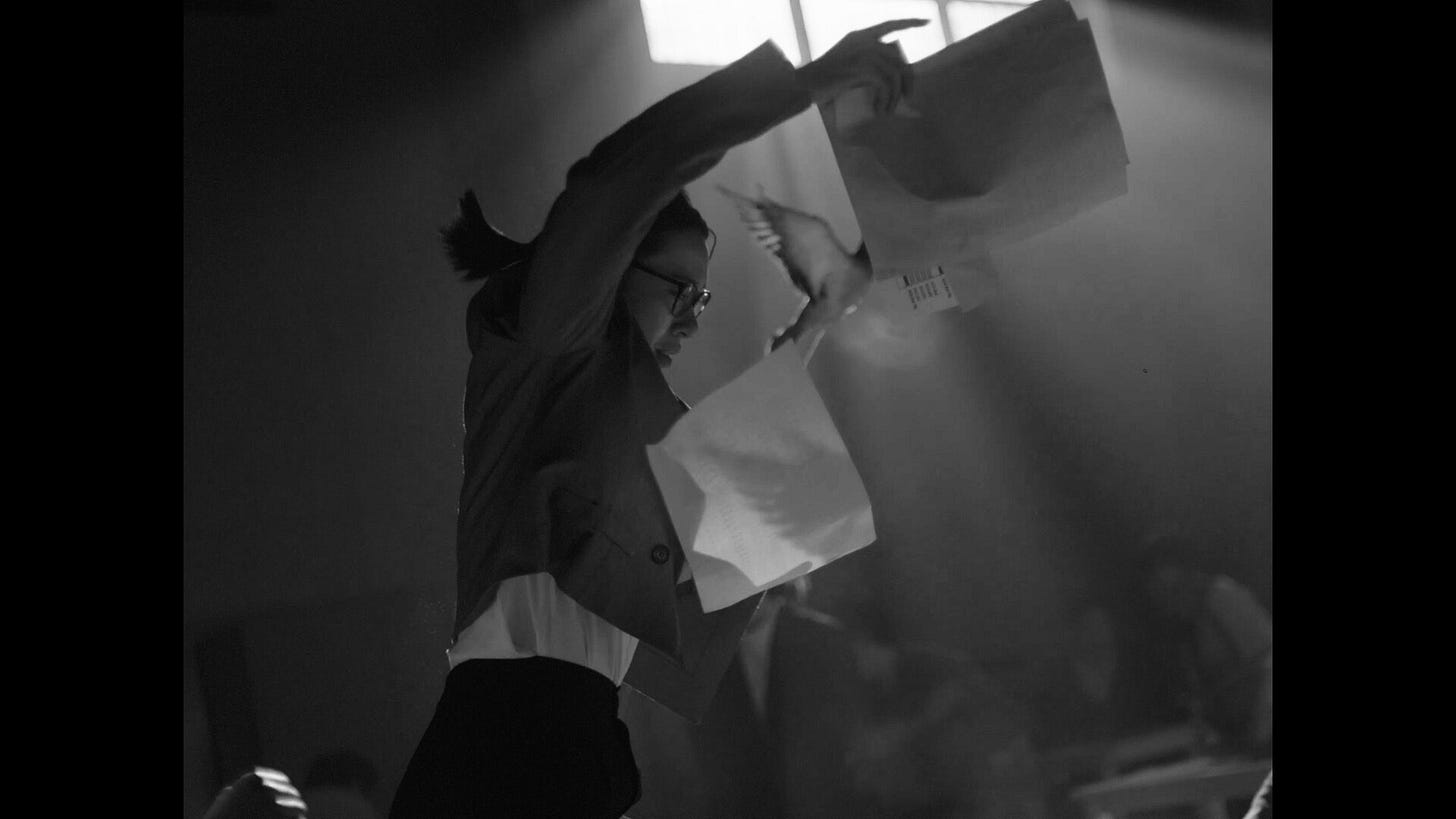

The dancing unfolds in a tour de force of editing, music, choreography, and precise camerawork, as the workers’ daily actions of entering data, stamping documents, and straightening piles of paper are all structured into precise, propulsive rhythms, a kind of massive percussive dance of office work, creating the sense that the demands of the workplace have an unstoppable inner force and logic, overpowering the humanity and individuality of the people who perform the work.

The choreographic style blends elements of jazz, release technique, and tap, using massed blocks of intricately interlocking rhythms to create a sense of the intensity of the work, and the requirement that workers merge seamlessly into their corporate functions. The intense kinetic propulsion of the movement, it’s rhythmic excitement, and the emotional commitment and precise technique of the performers, aided by the skillful structuring of the editing, combine to riveting effect, continually building the feeling of inner tension. The richly textured music, perfectly integrated with the choreography, is by the director. The music might be described as techno-disco, combining drum machines, electronica, and rhythmically sampled sounds such as water dripping.

In a strikingly choreographed sequence set in the cafeteria, the workers’ lunch time is just as regimented and regulated as their work. The serving and eating of food proceeds like clockwork, until one woman (Gong Xingxing) drops her bowl on the floor, causing everyone to stop and stare, amazed. The slightest non-conformity seems like an assault on the smooth functioning of the system. Her shame at her interruption is extreme, as she picks up her bowl and slinks away. Later, she will be publicly humiliated for her transgression, while the other workers pretend not to notice.

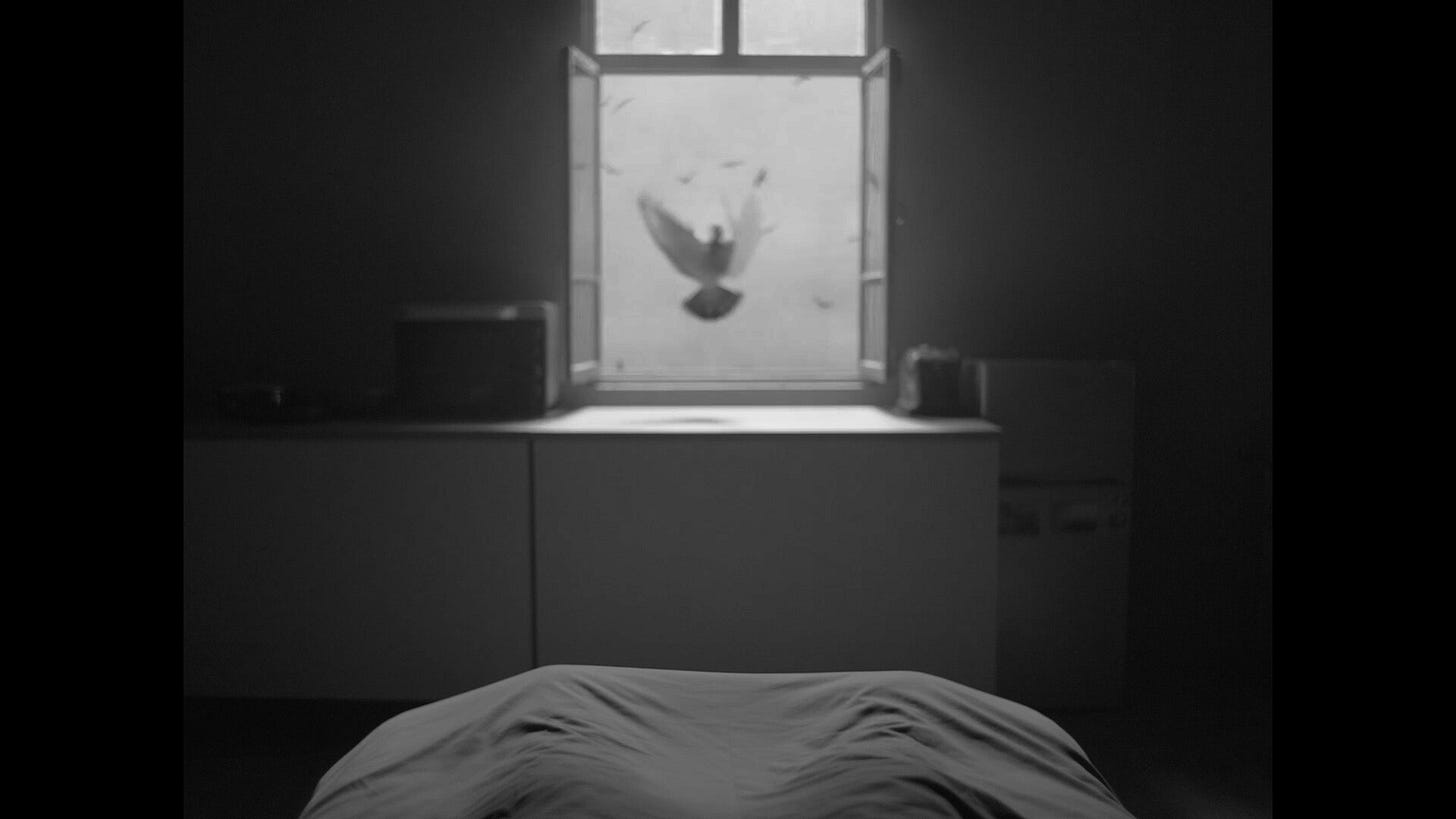

The relentless energy and music-video style cutting of these ensemble scenes is well balanced with quiet, intimate passages, in which a young male office worker tries to work up the courage to offer some compassion to the outcast woman. The world seems to hold its breath for a moment, when these two outcast spirits watch, mesmerized, as a bird feather falls through the light.

The release technique style of the movement allows the dancers to use a vocabulary less precisely shaped than typically seen in jazz dance, a choreography of inner impulses, well-suited to express the inner turmoil the characters feel, in response to their depersonalized, unrewarding existence. At the same time, the precision and musical sophistication of jazz allow the dancers to build up compelling group dynamics, emphasizing the relentless demands of the mass society. Zi Wei marries the mass spectacle of jazz to the restless interiority of post-modern dance. It’s a potent mixture.

The young man (Wang Zhenbing) is seen in a remarkable solo, walking through the building among masses of workers, all walking in lockstep. His unstable tremors and convulsive outbreaks, timed precisely to a drum solo, emphasize how much his inner distress is at variance with the outer conformity of the others.

The birds, who are occasionally seen entering the workspace through open windows, are continual irritants, reminders of the free, natural state which has been stolen from these people. Eventually one these birds creates an outbreak of panic and chaos in the office, a choreographed crisis. This panic, this hysteria about the “enemy” and the “emergency,” seem to be a necessary element of control, enforcing the overall totalitarian system. It’s like a classic communist “struggle session,” and the hapless woman who dropped the bowl is the unfortunate chosen target.

In the film’s ending sequence, a torrential downpour seems to transform everyone. It is as if the rain is a voice from heaven, the raindrops brilliantly lit and glistening, a faint voice, recalling them to their ancient lineage as animals, residents of planet earth. For the first time, their movements become fluid and graceful. Their movements are now highly individualized, no longer in lockstep unison, although still in an elegantly structured counterpoint. This, in turn, disrupts the uniformity of the office environment, and the tables and chairs are gradually rearranged so that they are each oriented differently.

In a society and a workplace that demands outward conformity and obedience, it can be hard to sense the individuality of the workers, their dreams, their regrets, and the damage caused by the effort to keep everything hidden. Dean Wei and Zi Wei have used the choreography of bodies and the choreography of cameras to make these hidden inner worlds become visible. These “worker ants” do indeed sleep, and also dream. This film allows us to glimpse these dreams.

My articles on experimental film are freely available to all, but are supported by monthly and annual donations from readers. Please consider becoming a paid subscriber to support my work. Thank you.