Veteran experimental filmmaker Dominic Angerame has been making work since 1969, and his films have been seen in many venues around the world. I recently took a look at some of his shorts, ranging from the 1980s to the present.

Battle Stations: A Naval Adventure (2002) presents footage shot at the naval shipyard at Hunters Point, San Francisco, which is juxtaposed with a sensual belly dance performed by multi-talented artist Leyna D’Ancona. (The accompanying Arabic music is not synced with the choreography, which can be rhythmically disconcerting to watch.) The tanks, trucks, and industrial trash of the site are superimposed, at one point, over the dancer’s undulating belly. Her feminine creative power, emanating from her center, contrasts with the industrial mechanisms of death and defense being practiced by the navy.

Akin to the West Coast spirit of Kenneth Anger, the film functions like a magical act, casting D’Ancona’s creative energy, like a spell, over the naval yard. The film is like an alchemical experiment, mixing opposing energies, simply to see what can be constructed from the naval/navel adventure.

Revelations (2020) is a 22 minute black and white study of the shipyards and downtown sections of San Francisco. The film, filled with elegantly superimposed sequences, consciously continues the “city symphony” tradition of filmmakers like Vertov (Berlin) and Clarke (Bridges Go Round), and surely makes its own contribution as a portrait of the industrial underside of San Francisco, with the Golden Gate and Bay bridges occasionally glimpsed in the background. For a film depicting the large, powerful machines of the shipyards, the pace of the film is oddly dawdling, as if the men who work there are merely puttering about in a garden on a long afternoon.

The cranes and shovels, with their ungainly mechanical claws, looks like giants, struggling to pick things up with their badly-made hands. Men in hard hats slowly, without apparent purpose or order, go about the business of moving piles of things from one place to another. Their work echoes the work of film editing, a lengthy exploratory process of moving around shots and images into different sequences, trying to uncover meaning and beauty and wholeness from the disparate elements.

Magnet cranes lift scrap metal from containers. Men criss-cross the space, carrying buckets and shovels. The dreamy, shimmering music (by Kevin Barnard) complements the languorous pace of the scenes, where massive and sharp materials are generally handled slowly and carefully. Beautiful montages of soaring towers in downtown San Francisco emphasize the powerful public face of a city, and its contrast to the ruined industrial garbage heaps where the castoff materials of construction are discarded.

In the film’s final sequence, we see the expanse of the Bay opening up, and watch slowed-down footage of waves crashing on the rocks underneath the Golden Gate Bridge. Overexposed footage, in which the crests of waves turn pure white, gives the feeling that an ocean of light, rather than water, is rolling towards us. The film’s sadness, surveying the Sisyphean task of workers dwarfed by a landscape of decaying industrial garbage, gives way to a benediction of peace, and a promise of a larger beauty, surrounding the endless toil.

Voyeuristic Tendencies (1984) consists of surreptitious shots of women standing near the windows of their apartment building in various stages of undress, shot from across the street. It confronts, in an obvious way, notions of violation and intrusion in filmmaking. While in one sense, Angerame is committing an aggressive and hostile act by shooting half-dressed women without their permission, it would be hard to argue that their unwilling appearance in this rarely screened art film is causing them any lasting or serious harm. One also has to note that these women are choosing to undress directly in front of an open window with no shades or curtains, one which faces onto the street. In any case, none of them are shown in a fully indecent state. (Well, almost none of them.)

The soundtrack to the film is a series of Eurythmics tracks. The song lyrics have no obvious relationship to the film, although a line from their best known song does seem relevant to the relationship of the voyeur to the object of his gaze: “some of them want to abuse you, some of them want to be abused by you.” The music, however, suggests the erotic atmosphere of a discotheque.

Men are shown in the window only one time, and it is telling that the men instantly recognize that a guy across the street is filming them. They sarcastically expose themselves to the camera.

The film certainly expresses a kind of obsessive fascination with women’s bodies, a fascination which is quite common in men, and it can seem like a kind of madness, dominating one’s thoughts at all hours of the day and night, as if a crazed maniac has control of you and is preventing you from focusing on the ordinary business of the day. Ogling women who don’t know they’re being observed adds a nasty thrill, as if you’re stealing from them, like a boy snatching a girl’s panties from her laundry hamper. Nevertheless, the film is long, and it essentially repeats the same idea over and over, with the same kind of music throughout. If you don’t share in the obsession, it can be difficult to maintain one’s attention for 17 minutes.

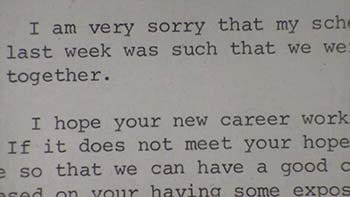

Hit the Turnpike! (1984), is a three minute film, humorously accompanied by the song Hit the Road, Jack, consisting of a rapid collage of Angerame’s many rejections from film festivals, distributors, and venues. As a filmmaker, I also have also received thousands of rejections, so I’m in full sympathy with Angerame’s idea. The film is not in any way a pity party or a resentful snarl at the world’s lack of appreciation of his artistry, because the quick pace and witty, upbeat music turn the film into a wise, bemused chuckle at the artists’ life, in which he must learn to let endlessly repeated rejections roll off of his back as if they were nothing. Then again, even in the film’s short duration, Angerame expands the film’s focus by widening the theme from his own rejections to the notion of rejection generally, including found footage clips of failed athletes, street beggars, etc. Most insouciant of all, the film ends with a shot of a man water-skiing down a flooded city street, tethered to a moving car. If life sends me disaster, Angerame seems to say, I’ll just have to ride along, and have a blast doing it.

My articles on experimental film are freely available to all, but are supported by monthly and annual donations from readers. Please consider becoming a paid subscriber to support my work. Thank you.