The Thing With Feathers: The One Who Hopes

(2025)

At the start of The One Who Hopes, a new feature length film by Stratis Chatzielenoudas, we see the sun rising over a quiet cityscape. We hear a conversation between two women, describing an interstellar voyage they have taken from a distant planet, a trip which has taken over 1000 years. (It quickly becomes apparent from context that one of the two voices belongs to a computer.) The images of the city progress rapidly from long shots to mid shots to closeups: a series of strikingly framed, beautifully edited moments, all showing desolate, ruined features of the city: a junked car, a rusted fence, a plastic bag flapping in the wind. No people are visible.

We see a shot of a ferry terminal in Perama, Greece, where the English artist Robert Montgomery has installed the words “The Beginning of Hope” over the entrance. The human narrator observes “hope makes long journeys less boring.” We see a man on the dock, staring expectantly up at the sky. This prolog to the film sets all of the themes of this poetic documentary essay in motion: the hope of renewing a decaying, ruined culture, the longing for connection with others, and birds as a symbol of that hope, the hope of a liberated future where the human community is reconstituted, the hope of a life in which people can be as free and as interconnected as a flock of birds.

Chatzielenoudas has created an original and effective dual structure for the film. On the soundtrack, the conversation between the astronaut and her AI companion unfolds as a poetic and metaphorical narrative. Their home planet is a world which has lost the ability to use language, and they are seeking a world where there is still a population of birds, whose constant musical chatter offers a way to regain the ability to communicate, but this image must be understood as applying to our own world metaphorically. On a literal level, the advent of the internet has increased the amount of verbal communication in our world exponentially, but as this glut of language floods our awareness, the value of words seems to drain away proportionally. Our ears and eyes are bombarded with more and more language, and naturally we listen less and less. Pointedly, it is the advent of AI which is the primary accelerator of the degradation of meaning in our language, as the online world is increasingly flooded with messages which have been written without thought and without awareness, a development which is eerily embodied by this story of a lonely traveler, whose only companion is a simulated being.

The film’s visual story addresses the same things, but on a parallel track, through episodes of documentary footage, showing members of a society of canary breeders, hoping to breed birds which are such extraordinary singers that they will win a competition. We also see a community of homing pigeon breeders, releasing birds from their roofs and waiting for them to return, as well as workers on an assembly line at a recycling plant. These episodes can all be understood, in the context of the narration, as expressions of our human fascination with the complex social life of birds, and our efforts to sift through the detritus of our polluted world and try to reclaim something of value.

At times, Chatzielenoudas draws points of contact between the film’s two parallel tracks. We’re watching a vast container port at a harbor, and the traveler remarks that, in her spaceship, she’s arriving in our world “like merchandise in a box.” These moments of cross-reference between the narration and the visual story encourage us, while watching, to find our own points of connection between sounds and images. Mostly, the visual and verbal stories progress independently, each shining light on related poetic concerns, but looking at them from different angles. This provides the viewer with a creative and active mode of viewing, where underlying connections between the two narrative strands constantly pop into our awareness.

One secret to how these two strands, the verbal and the visual, are kept in balance is that, on the whole, the visual sequences predominate. For example, we are given the opportunity to watch a canary bathing in the the water dish in his cage, and we have plenty of time to absorb his rhythms and habits. This leisurely pace, only occasionally punctured by comments from the narrators, gives the film a contemplative feeling, with time to let images, sounds, words and thoughts recombine, sparking new insights.

The sequences of the canary breeders are a particularly poignant expression of the complexity of our relationship to the natural world. On the one hand, by keeping these birds in cages and making them compete in song contests, the breeders are depriving the birds of the one quality which makes them most beautiful to us: their freedom, their ability to roam the skies. In the contest, the songs are judged by humans according to criteria that likely are completely irrelevant to birds. Male birds in the wild sing to compete with one another for a mate, not to win a trophy in a competition. On the other hand, as we watch the breeders meticulously clean the cages and fuss over their birds, it is clear that they love and revere these creatures. As is typical of the complexity of ecological relationships, the market for competition canaries is both protecting the birds and accelerating their extinction.

The astronaut hopes to relearn the secret of language from birds, and the canary breeders, whom we also hear discussing the relative merits of different birds as singers, are likewise trying to decode the essence of their language, but their human framework of understanding stands in the way. They may learn how to breed prize-winning singers, but they’re not going to go out into a forest and start conversing with wild canaries. Even within the breeders club, the Spanish-speaking breeders have trouble communicating with the Greek-speaking breeders.

Shots of stacked rows of canary cages are intercut with sequences of anonymous, high-rise apartments blocks, a visual rhyme which emphasizes the similarities between modern urban life and the lives of the caged birds. Like the birds, both our physical structures and our social and political structures are training us, breeding us, to “sing,” to produce the goods which are so valuable to the managers and owners, even if they understand little about what’s going on in our souls, in our longing to regain our lost freedom.

At a huge landfill, masses of seagulls wheel overhead, calling constantly. They have learned to make a living off of our discarded trash, and are likely being poisoned by our toxins as well. The narrator comments that the destruction of nature leads directly to the destruction of culture, of human hopes and aspirations. She acknowledges that her mission to save culture through birdsong is likely futile, but makes a reference to Camus’ gloss on the Greek myth: “one must imagine Sisyphus happy.” It is the effort to re-connect which, in and of itself, creates the meaning which is being sought.

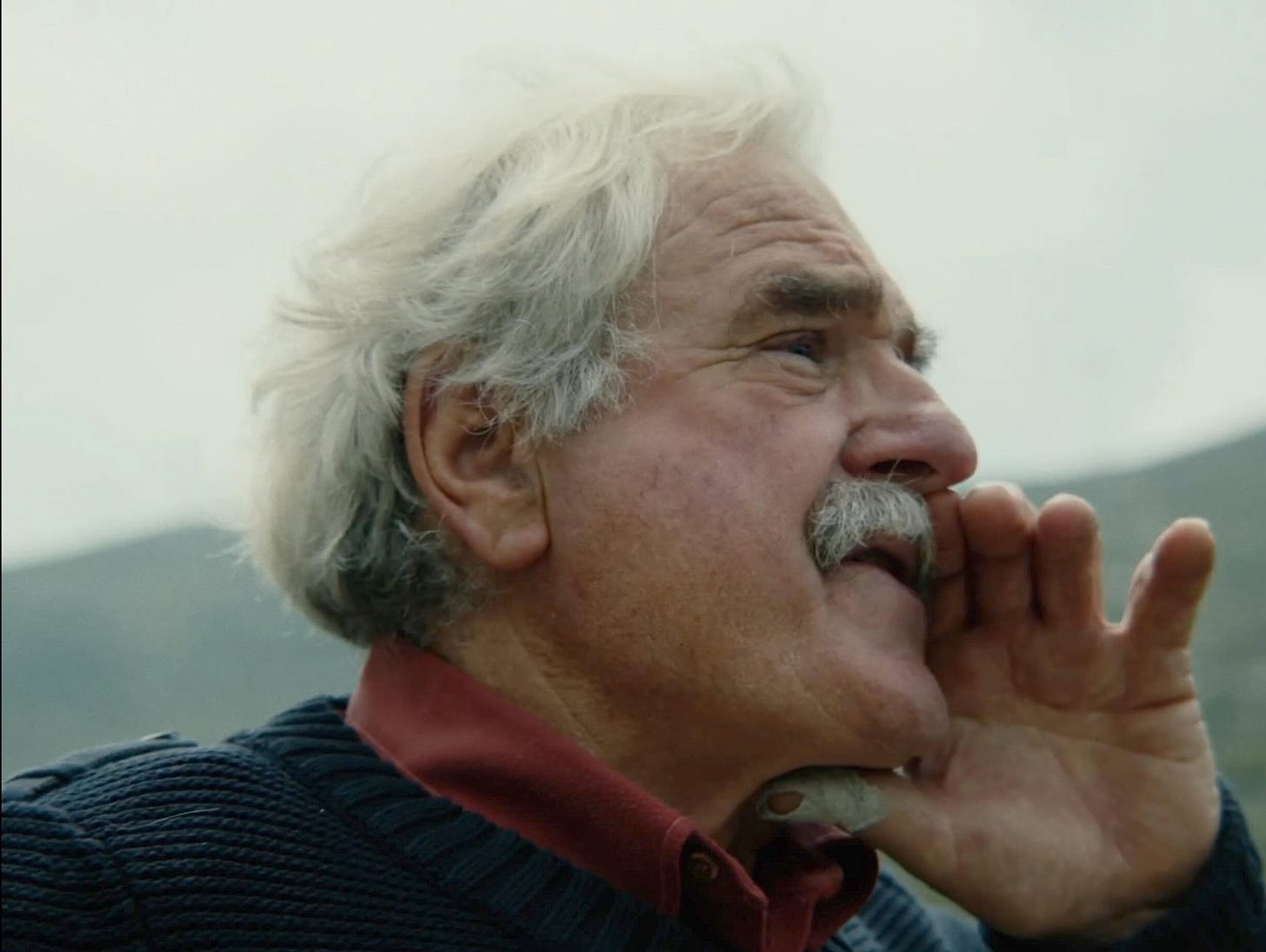

In the film’s surprising final chapter, we land in a remote mountain village on the Greek island of Evia, where the inhabitants communicate with one another across the hills using Sfyria, a language which translates ordinary Greek into complex whistles. Syfria is an ancient language, and according to a BBC article, only six active speakers remain, as the inhabitants of the village dwindle. Subtitles translate their whistles into English for us. In this remote corner of the world, there are still a handful of people who have learned language from the birds. Meanwhile, the constant grinding sound of wind turbines on the hills not only makes it harder to hear the whistles, but the turbines pose a serious threat to the local birds. The narrator comments that the turbines represent a desperate attempt on the part of humans to atone for the damage they have caused. The countdown to extinction accelerates.

As promised in the title, the film ends on a hopeful note. The astronaut is ready to return home, with renewed belief in the possibility of saving her dying planet. Even at their darkest hour, humans are touching in their persistent drive to find a way to connect with others, and even the computer admits that she is touched by this. Hope does more than make the journey “less boring,” it’s the thing that makes the journey possible. As Emily Dickinson wrote, “Hope is the thing with feathers.”

My articles on experimental film are freely available to all, but are supported by monthly and annual donations from readers. Please consider becoming a paid subscriber to support my work. Thank you.