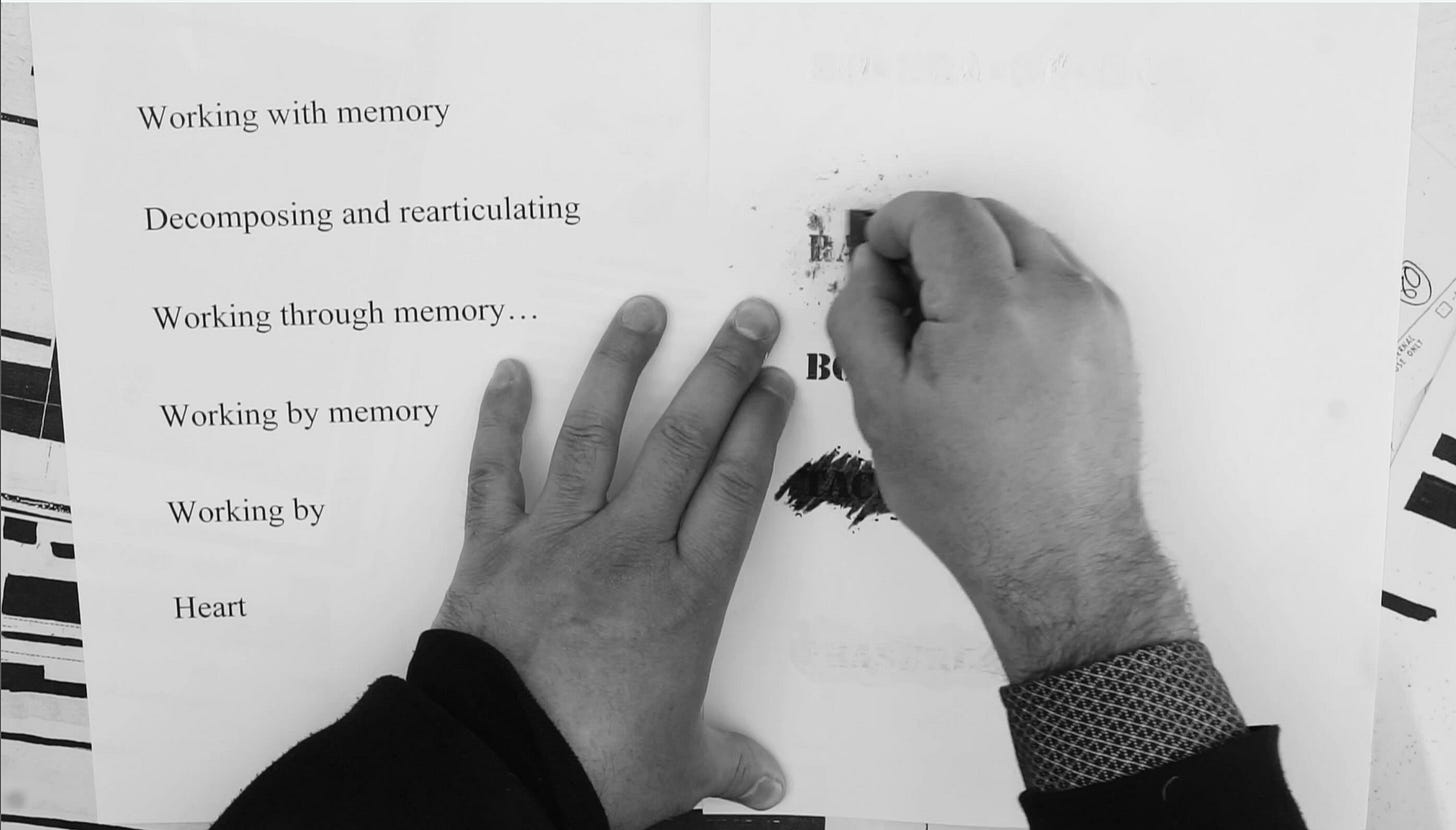

Borradura is a 13 minute film by the team of Camila Estrella, Bárbara Oettinger and Carlos Soto Román. The entire film focuses on watching a pair of hands which are painstakingly blocking out printed text. There are two sorts of documents being blotted out. There are declassified papers, released under order by the Bill Clinton administration in 1999, which document the CIA’s funding and orchestration of the coup on September 11, 1973 which toppled Chile’s democratically elected president Salvador Allende and installed the military dictator Augosto Pinochet. The documents also provide evidence of the subsequent support and training which US intelligence provided to the Pinochet government. When originally released, these documents were already heavily redacted, with many blocks of text blacked out. They were finally released in un-redacted form in 2023, two years after this film was made.

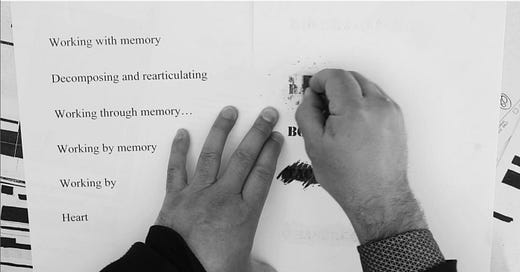

The other text which we see being covered up are pages of Soto Román’s poetry, poetry which also forms the text of the film, which is heard on the soundtrack throughout. The poem uses precise imagery to meditate on the CIA’s act of covering up the evidence of their crimes, what Soto Román refers to as their “history-stripping operation.” Their erasures are seen as a further insult to the people who lived under the dictatorship, an attempt to obliterate their memories and feelings, which only adds to the suffering caused by the fear, the killings, the disappearances propagated by the regime. The poet’s defiant act of willfully completing the erasure of history, and furthermore erasing his own poetry, comes with its own dangers:

How to compromise the documents of suffering without turning oneself into a document of suffering…

The text constantly intertwines Spanish and English, emphasizing the interlocking complicity of American and Chilean actors in this history. Part way through the film, the Spanish passages are heard in English translation, and vice versa. The narration begins with Soto Román’s voice, and his voice is gradually blended with the overlapping words of the other two filmmakers. This palimpsest of voices is not so much the sound of erasure, but more of a multiplicity of voices, clamoring to be heard. It is the voices of the disappeared, first silenced by the regime, and later by the secrecy of the CIA.

One by one, the empty words disappear…

accepting the transition from cruelty to secrecy

from the secret to the grave (a la urna, which can also mean “to the ballot box”)

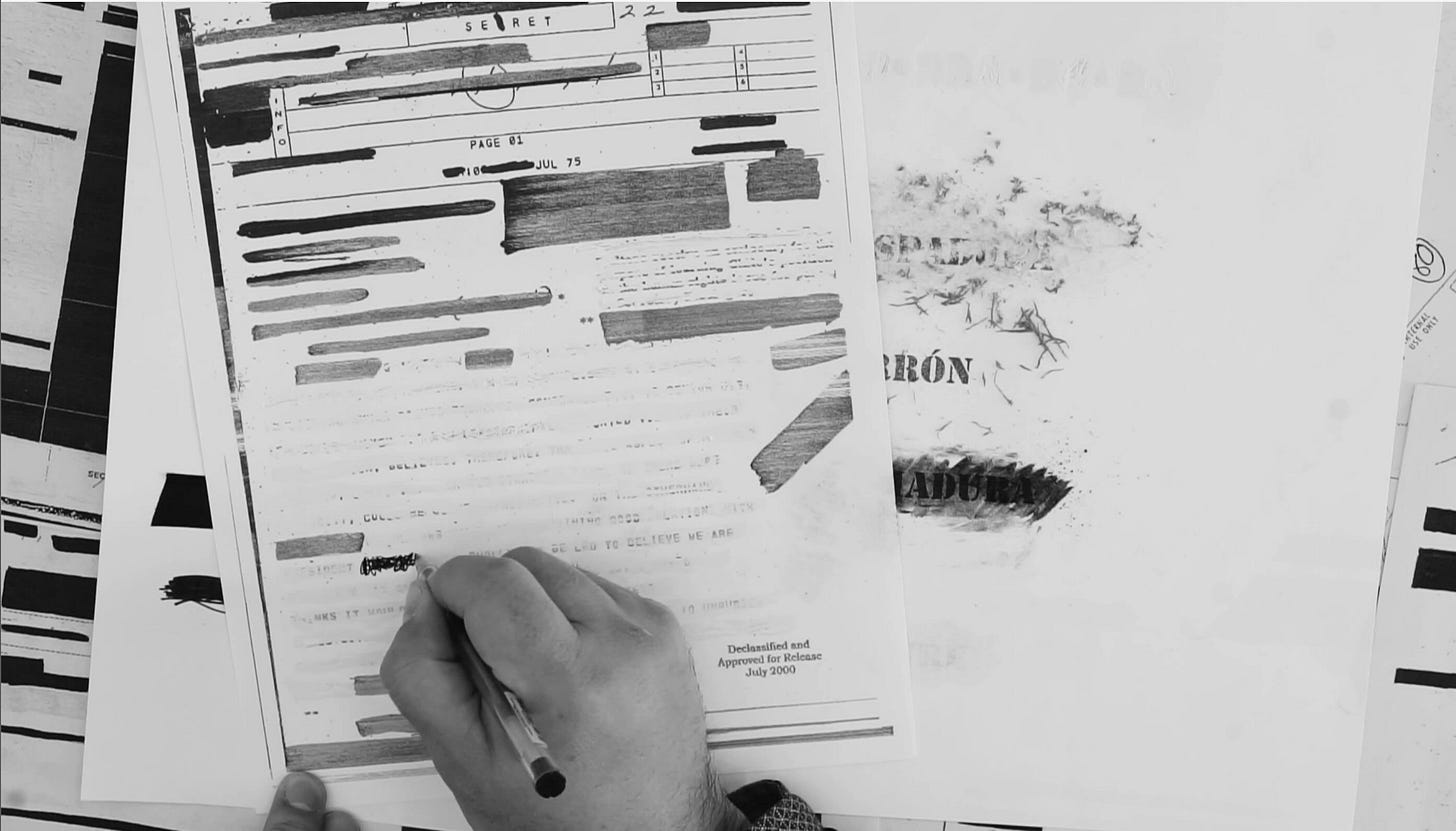

from the grave to the document…The hands cover up the text in many different ways: covering the words with white-out fluid, black marker, rubbing out with erasers, smearing white powder from capsules onto the words. The footage is sometimes shown in negative, so that white marker is drawn onto white text on a black page, making the obliterated parts of the text glow with a strange luminescence, glaring omissions in the public record. The erasures are relentlessly physical, tactile. Far from doing a neat job of carefully blocking out the words, the hands leave wet gobs of paint on the paper, parts of letters peeking out, or vigorously rub the paper, transforming it into fuzzy shreds.

Despite President Clinton’s order, the CIA declines to confess their crimes, and it is beyond the poet’s power to force the hidden information out into the public eye. The film depicts an attempt to physically wrest power back from this impasse. The pages may be hiding the verbal record of the crimes, but the poet’s hands, covered with smudges of ink, of charcoal, of paper dust, are relentlessly transforming the papers from occluded texts into textured, tortured objects. Close-ups on covered-up words turn the scribblings of a ball point pen, obliterating the name “Pinochet,” into a dense, energized cloud of revenge. It forces the confessions out of the paper, just as surely as the secret police can force confessions out of a tortured detainee. Reluctantly, they give up their truth as physical objects, conglomerates of wood pulp and ink. It is almost as if the bodies of the disappeared have been disinterred and flung onto the grounds of the Palacio de La Moneda. Physical facts trump verbal obfuscation. This act of restoration through intensifying the erasure is a powerful instance of poetic alchemy, a magical rite to restore the dead.

The words are repeatedly covered by heavy charcoal marks, which are immediately smeared by the fingers, partially revealing the words once again. With each new layer of smeared charcoal, the page turns from poetry to drawing, from thoughts to images, to a contested, multi-layered history of stories hidden and revealed, over and over.

Why must the documents be coherent, when it is precisely the order we wish to subvert?

Dictatorship, with its obsession with order and control, oppresses by eliminating those who resist the orders. By destroying the verbal content of the CIA’s files, wiping away their calm, orderly account of the catastrophe they unleashed over Chile, the poet subverts the murderous logic which conceives of and carries out such policies.

In a lucid expression of his artistic intent, Soto Román writes:

The poet as historian The poet as archeologist Has the responsibility To silence the text To make room for another

The American government has had its say. It has written the text of North American power, covering over the revolutionary program of Allende and his movement. It’s time, finally, for them to shut up, and allow us to listen to the long silenced voices of the Chilean people. To give silence, as Soto Román insists, “the importance it deserves.” Borradura turns government documents to dust, and allows us to see that the dust itself is the message.

My articles on experimental film are freely available to all, but are supported by monthly and annual donations from readers. Please consider becoming a paid subscriber to support my work. Thank you.