(This article previously appeared in Film International.)

Frozen is an experimental short by Adonia Bouchehri, a young London-based artist. Fascinating and wise, the film examines the creative process in a form which is part prose poem, part surrealist adventure, and part TV cooking show.

As the film begins, we see a young woman slowly rubbing a mysterious black object, which is encased in a block of ice. Then we see her preparing a dish which involves stuffing a whole fish with vegetables. A narrator’s voice offers a series of instructions, somewhat in the manner of steps in a recipe, but these instructions are clearly meant metaphorically:

“Don’t try to grasp the image prematurely. Open it; you see that it’s empty. Begin to feed it.”

As we watch her preparing the fish to be placed in the oven, and continuing to rub the black object, the narrator develops the steps needed in order to prepare an “image.” As the recipe continues, it becomes clear that the central metaphor of the piece is that when an artist first thinks of an image or an idea, it appears in a crystallized, “frozen” form, and it must slowly, patiently be allowed to “thaw” in order to reveal its inner heart and outward form. This notion might sound strange and elusive, but it will be intuitively familiar to most people who have engaged in creative work.

Bouchehri’s point of view about the creative process is that one shouldn’t give up prematurely on an image or an idea, simply because it doesn’t immediately yield spectacular results. She advocates a lengthy, patient practice, in which a creative idea, which at first seems unpromising, can be made to yield artistic treasures, if only the artist has the courage, forbearance, and willpower to gently, slowly, nurture the image and allow it to grow organically and blossom into its full form. This is an artistic philosophy which is exceedingly rare among younger artists nowadays. We live in a time in which software promises that one can produce wonderful images or films with barely any effort. Absorbed in our phones, we endlessly scroll back and forth between apps, giving cursory glances at each post, and quickly moving on, as soon as any statement seems to demand effort, thought or empathy. Bouchehri, by contrast, believes that any idea or image which comes to you can become the basis of a wonderful work of art, provided that the artist patiently listens and probes into the idea, searching for its inner vibrance, and skillfully cultivating it, the way a gardener cultivates his flowers and shrubs. If Bouchehri possesses so much independence and wisdom at such a young age, surely her artistic adventures will lead her on to do great things.

In the middle section of the film, the narrator develops her instructions so that they move beyond the metaphor of cooking: “Tell a story,” she advises. “Let the story circle around the image, but make sure never to let the story touch the image itself.”

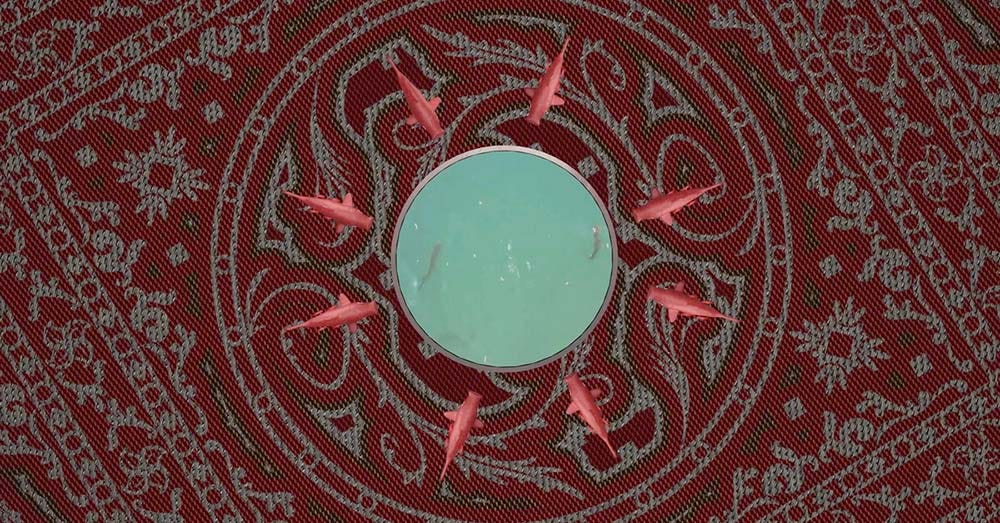

Following her own advice, she begins to tell a story about a woman who is watching a film about salmon swimming in a river. The woman encounters a certain young man, who offers her a glass of rosé wine. While listening to this story, we are watching a surreal and beautiful 3D animation. Teams of pink, plastic fish roll along a carpet on little wheels, rolling past a series of mushrooms growing in terrariums, each warmed by its own light bulb. The images do not directly illustrate the story, but refer to it metaphorically. We don’t see the young man, but the rosé color of the wine suffuses everything on the screen. The fish, gliding effortlessly on their wheels, are like artistic ideas which are allowed to effortlessly seek new terrain. The mushrooms are being slowly cultivated, just as the narrator had recommended we cultivate the “image.”

One of the fascinating things about Frozen is that the film itself is an embodiment of the advice given by the narrator. The film develops its ideas exactly as the narrator recommends, beginning with the image of the fish, and using an indirectly related story as a way to develop the image further. The technique yields strangely compelling results, images which are both surprising and satisfying. The film simultaneously describes the creative process, and brilliantly carries it out.

The realistically rendered surfaces in the animations have very detailed and particular textures: gleaming milky marble, a rug which is seemingly under a sheet of glass. But the noiseless movement of the wheels and the plastic sheen of the fish mark this as an imaginary world. It’s a frozen world. Specific clear textures within a weightless, artificial universe: the precise hallmarks of the imagination. A pink dog appears on wheels as well, and as soon as he is out of frame, we hear the echo of his bark. By detaching sounds from images, Bouchehri gives them space to develop independently from one another.

As the narrator continues her “recipe” for the final stages of finishing the image, one piece of her advice is to “take your time and look at the image.” Intriguingly, this statement accompanies a brief shot of an older woman with her head on a table, turned towards the fish. This is immediately followed by a shot of the original young woman in the same position. The change in age is a clear reference to the idea of “taking your time,” but by showing us the older woman first, it implies that the contemplation of the image allows us to absorb an older, wiser version of ourselves into ourselves, even while we are still young.

Finally, the black frozen object which she has been patiently rubbing and thawing throughout the film finally thaws, and we see that it is a black dress (the same one that the older woman wore.) The narrator tells her to “step inside” the image. By recommending that she “wear” the image, she implies that the final stage of the creative process is for the artist to fully inhabit the image, to identify with it, and live from inside of the image’s point of view. This advice, known to every good novelist, actor, playwright, or visual artist, is what allows the work to come alive, to speak as if it has blood flowing through its veins, no matter how abstract its outward form is.

Frozen is a hybrid work, part artistic primer, part manifesto, and part visit to a strange pink planet of toy dogs and fish. It might take viewers a few moments to warm up to its unusual form and message, but anyone who is engaged in creative work would do very well to follow its recipe.

My articles on experimental film are freely available to all, but are supported by monthly and annual donations from readers. Please consider becoming a paid subscriber to support my work. Thank you.