Binary Love, a 13 minute film by Ewan Golder, takes us into a floating, disembodied world in which love, desire, and human connection are no longer visceral, physical realities, but are simply simulated shadows in a virtual environment. The film begins with a futuristic “dating app,” capable of matching two sleeping people inside of their dreams. Eugene and Jessica, the man and woman who match up with this app, appear to be strangers searching for a lover, although we later discover that they are in fact a couple, lifelong partners. Perhaps they appear to one another in disguised form, as is often the case in dreams.

The title, Binary Love, describes the film on many levels. The film looks at love mediated by technology, by binary code. The film depicts multiple binary realities. The lovers are both strangers and life partners, asleep and awake, virtual and physical lovers, old and young, all at the same time. The film depicts an obsessive switching between these levels of reality, a liminal state in which these contradictory states are all equally true at once. It's post-truth love.

The film itself exhibits a binary form as well: at once poetic narrative and music video. The imagery alternates between showing the couple floating in an imaginary, virtual space, and showing them on a film set, in front of rolls of green-screen paper and surrounded by video equipment, a frank depiction of the poetic, double nature of artistic expression: technical trickery which becomes emotional truth.

Eugene and Jessica prefer virtual reality to plain old reality, and their dialog makes clear that this is the result of a state of extremely deep depression. Jessica says that she is asleep because she is “dead to the world,” unable to cope with the stress of life. This is the film's underlying truth: a hopeless world where freedom is absent, emotional connection is impossible, and the only comfort is found in technological-assisted fantasies. “I exist to please you, my love,” says Eugene. This is the lovemaking of an icon, an online avatar, an imaginary being, technologically conjured for the purpose of addiction and enslavement. The lovers, helplessly in thrall to the fantasy, are only dimly aware of how the system is designed to manipulate them, which Jessica expresses by her sense that both of them are somehow “wrong.”

At one point, Eugene complains of having “a crappy connection,” which refers not only to a technological problem, but his underlying existential problem as well. He also complains that he has “lost his narrative drive,” another poetic phrase which evokes both the loss of an artistic, emotional drive and a computer drive. In yet another poetic double entendre, Eugene refers to their aging selves as suffering from “planned obsolescence,” a chillingly mechanistic description of the inevitable decay and death of living beings.

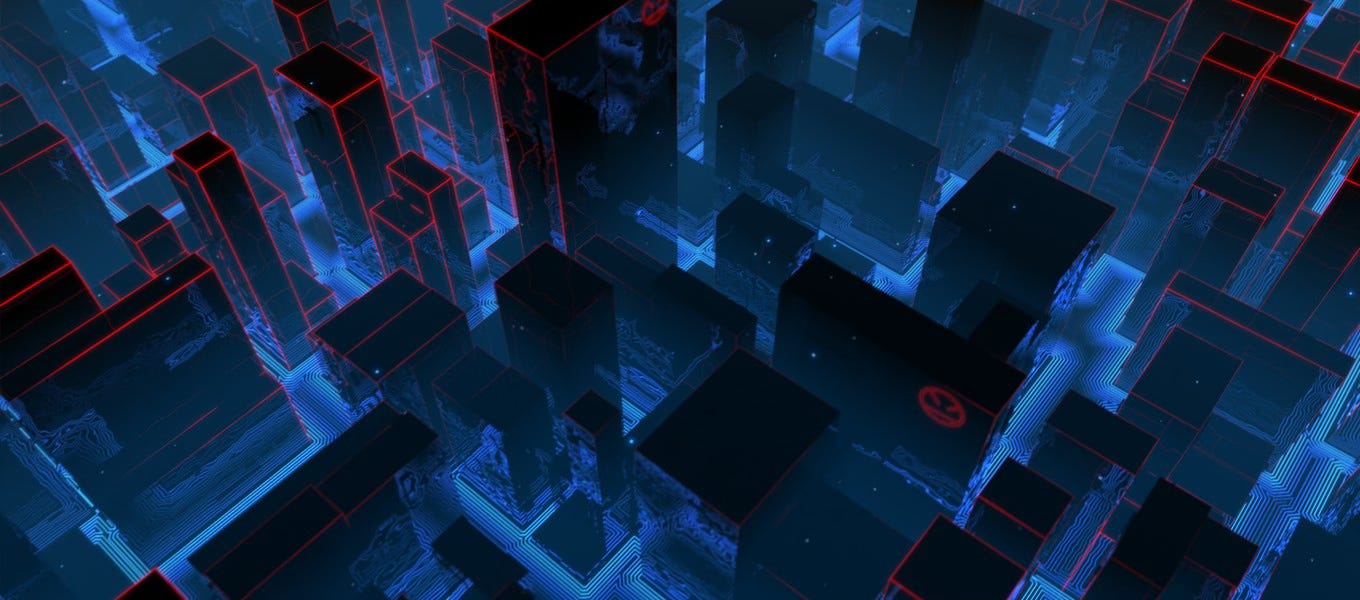

The shimmering animations by Pierre-Yves Boirasmé which form the visual background of the film use lines of deep blue and red suspended in a cyber-space of glittering stars, and forming themselves into pulsating cities overlaid with networks of electronic signals. The sound texture, created by Stanislav Makovsky, provides a slowly building wall of electronic tones, adding a deep urgency and drama to the film.

The plot of Binary Love is in the form of science fiction, set in a technologically advanced future, but this setting is used as a metaphor, a way of speaking about the present, about the collapse of meaningful human connection in our fragmented, technology-ridden culture. We've become swamped, overwhelmed by the seductive power of virtual spaces, by their endless supply of emotionally addictive, irresistible fantasy, rendering us incapable of simple human empathy or connection. It puts us in a lonely, hopeless place, making us even more susceptible to manipulation.

The lovers are each depicted throughout by two different actors, one old and one young, switching between the two freely throughout the film, in different combinations: both old, both young, one old and the other one young. This strategy suggests, at different moments, an older couple using technology to virtually re-create their youth, a young couple virtually imagining their old age, or an ambiguous, undefined state, in which all moments of a life co-exist, in the same way that all moments of human history and culture co-exist within the eternal present of the internet's vast repository.

The film's surreal climax comes with a music video of a catchy pop tune (created by the director), in which the lovers invite one another to “simulate with me.” They don VR headgear, and indulge in virtual love-making, in every possible combination of their young and old selves. This transformation, from dialog to song, from alienated chatter through the app to deliriously ecstatic fake connection, this transcendence of contradictory states of being, elevates the film onto an exhilarating, giddy level.

A closing image shows the young couple, sound asleep in bed, the morning alarm tone beginning to ring as traffic sounds drift in from the street. But this is not the “it was all a dream” plot device, which has been used to “explain” the endings of surreal stories since Alice in Wonderland. This particular state, an ordinary couple lying asleep in their bed, is perhaps the underlying physical reality behind all of the fantasies and dreams, but that doesn't make it more “real.” The insidious quality of our technologically-mediated lives is that it alienates us from our own hearts, minds, and bodies so deeply, that it can make all states feel equally empty and unreal. This is the tragedy of a culture veering into psychosis: the impulse to flee an intolerable reality is understandable, but living in fantasy worlds simply leads you to being wrong about everything, all of the time. Binary Love finds a subtle and poetic cinematic language to illuminate this conundrum.

My articles on experimental film are freely available to all, but are supported by monthly and annual donations from readers. Please consider becoming a paid subscriber to support my work. Thank you.