Making Noise: The Interruption

(2025)

The Interruption, a 20 minute short by Asreen Zangana, begins with its opening credits, accompanied by a cacophonous sound: a crowd of people, seemingly jeering, shouting acclaim, and booing, all at the same time. A woman (the mesmerizing Jan-Leslie Harding), wearing an elaborate headdress and a gown which features long white feathers at the ends of the sleeves, enters a bizarrely ornate room, carrying a platter with a tray of pasta arranged into fancy spirals. We hear thunderous applause. Her husband showers her with praise for this sumptuous meal, which elicits another round of applause. It seems we’re witnessing a performance, but a strange performance, as if a crew of enthusiastic, penniless artists had raided dumpsters and thrift stores, trying to recreate the splendor of a grand opera out of gaudy trash, the set and costumes a jumble of plastic flowers, piss-elegant furniture, and swatches of leopard-print fabric.

The ensuing drama presents a family dinner in which the husband continues to praise the dish of spaghetti and meatballs, intermittently making “asides” in which he expresses his secret revulsion for the “disgusting” meal, which is the same thing she serves every night. These asides are presented with the kind of exaggerated theatrical flourish that would put the most stylized Restoration actors to shame. (For some reason, he makes the asides underneath the dining table, speaking to a fish.) The daughter competes with the father, trying to outdo him in her hysterical love for her mother and her mother’s cooking, exhibiting an insatiable appetite for extra servings, while the son acts as if these nightly dinners are sheer torture for him. The performance style is uber-artificial. To call it overacting would be an understatement. The actors’ voices, imprecisely dubbed, only add to the feeling of unreality. The constant sound of crowd reactions reinforces the sense that every moment of this family dinner is a performance, for show.

Zangana’s film is clearly inspired by a much older style of American experimental film, the absurdist dramas, satirizing bourgeois behavior, of the early Jack Smith, Ken Jacobs, or the Kuchar brothers. More than anything, her brand of absurdist drama looks like something that could have been produced by John Vaccaro’s Playhouse of the Ridiculous company in the mid 1960s at the LaMama theater in New York, where, in fact, this film seems to have been surreptitiously shot.

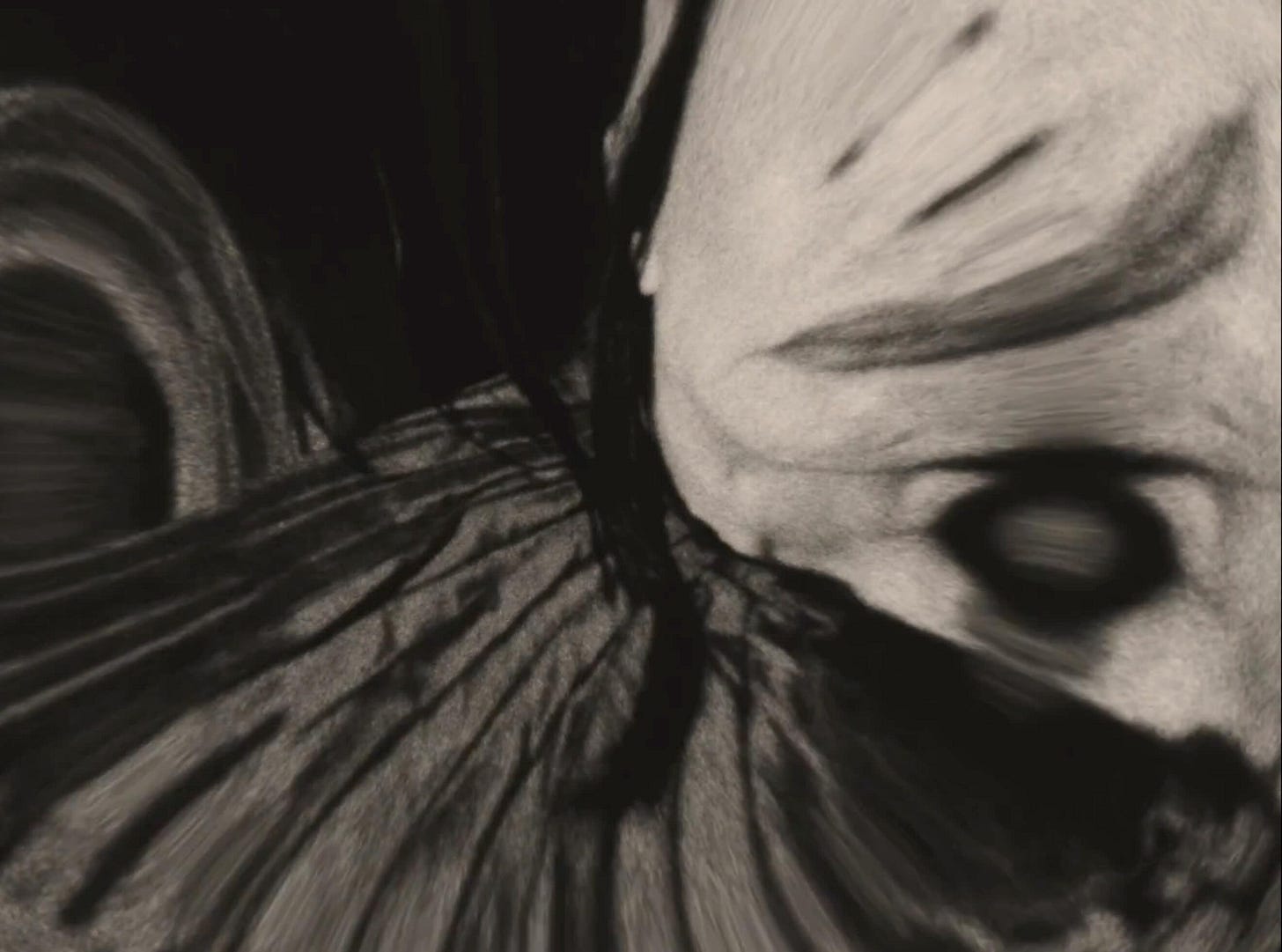

The scene devolves into chaos. In the corner, a singer dressed like a nightmare Pagliacci delivers an operatic onslaught, but only the mother appears to see or hear him. She becomes frantic and distraught, both from the music itself and from her confusion. As her mind breaks down, so too do the film’s images and sound, both becoming increasingly distorted.

The Interruption presents the triumph of artifice. The conventional, 1950s image of the happy nuclear family, the wife completely fulfilled by her role of making delicious meals for her family, is a farce. Everything that everyone says, at every moment, is brittle and false. The mother is tortured by her visions of opera, that most artificial of art-forms, yet everyone else continues to act as if everything is perfectly normal. Predictably, in the end, it is this opera singer who triumphs over the others, embracing the smelly, stinky fish of the father’s duplicity.

This style of absurdist theater and film may have passed out of fashion 50 years ago, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t highly relevant to our world today. By embracing an older style, Zangana introduces a new generation to the strange, unnerving delight of embracing life’s absurdity. One of the most common observations about our current world is that nothing seems to make sense, and everyone seems to have gone mad at once. Different groups of people live in alternate universes. As playwright Richard Foreman wrote: “Some of us are deafened by the noise—and some of us say: What noise? What noise?”

Foreman’s answer to his own question was “we’re making our own noise.” Zangana’s film begins with noise and ends with dissonant music, over black leader. By filling our eyes and ears with the constant noise of our own useless, worn-out ancient beliefs, she amplifies their absurdity, using the sheer power of her creativity, her imagination, and the crazy funhouse which her crew has constructed for us to shatter the power of these beliefs into shards of comic delight. Like a powerful drug, her film tears our sense of reality to shreds, and makes the whole experience into a crazy joyride.

My articles on experimental film are freely available to all, but are supported by monthly and annual donations from readers. Please consider becoming a paid subscriber to support my work. Thank you.