Light Through the Cracks: Monument

(2025)

Over the past few weeks, I have been writing about some films which I enjoyed at the Moviate Underground Film Festival in May 2025. This is the final article in the series.

Monument, a 17 minute film by Jeremy Drummond, opens with footage of a huge, jumbled collection of enormous concrete busts of 43 American presidents, currently residing in crumbling splendor in a field in Croaker, Virginia. The busts were created by late sculptor David Adickes for a Virginia theme park, which went out of business after a few years. They were slated for destruction, but the contractor hired to crush them decided to invest his own money to haul them off to his private property, where the surreal sight of these massive, crumbling heads is now attracting bus-loads of tourists. Adickes died this past week, at age 98, without succeeding in finding a permanent home for any of the three full sets of presidential busts he completed.

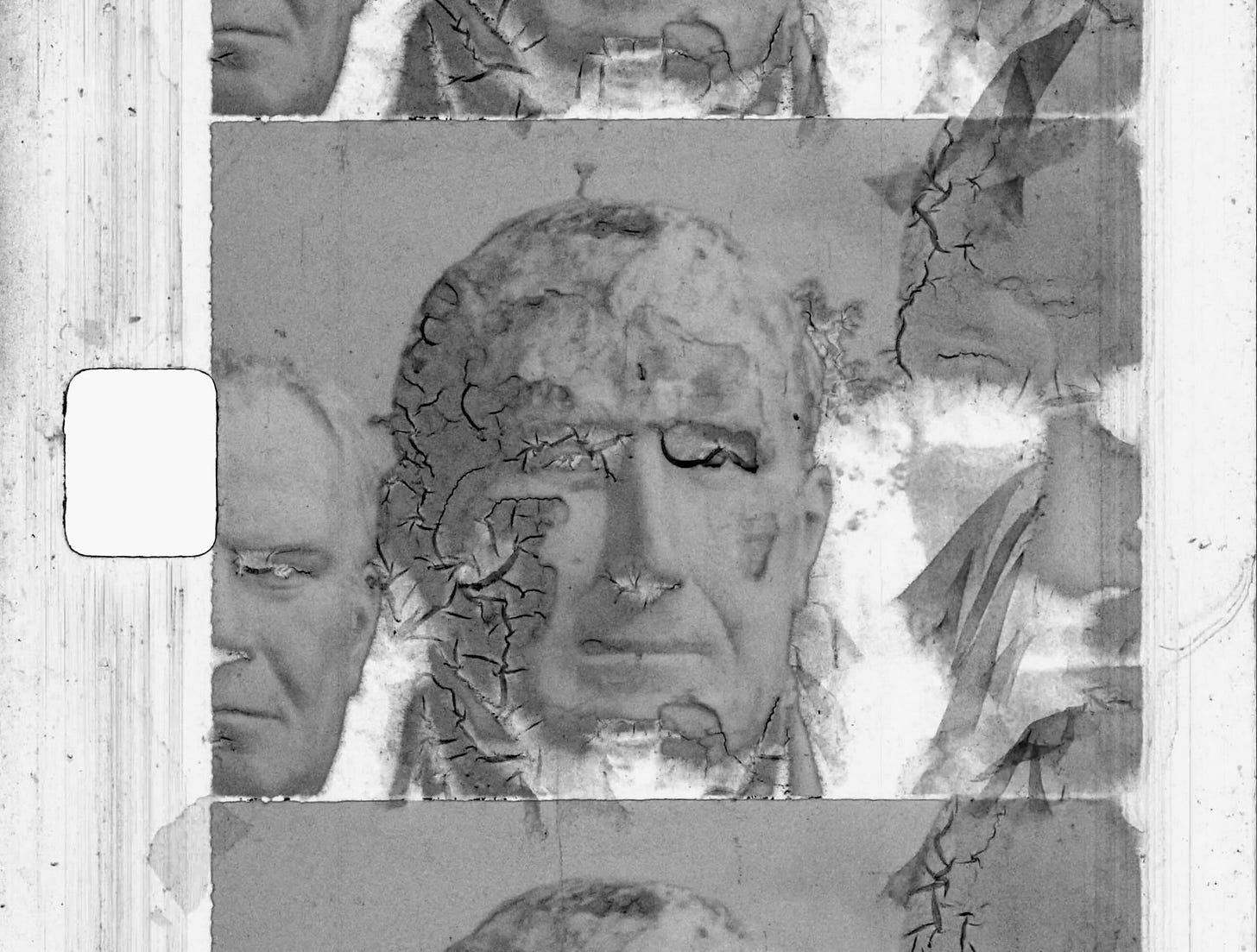

Drummond’s Super 8 footage is highly hand-processed and deliberately degraded. The grainy, black and white footage is covered with shifting cracks, splotches and stains. The grim presidential faces gaze down on us, exhorting us to live as exemplary citizens. The filmstrip itself is plainly visible, complete with sprocket holes, and the vulnerable, decaying material of the film closely echoes the physical decay of the sculptures and, one might add, our sense of the rapid decay of American democracy.

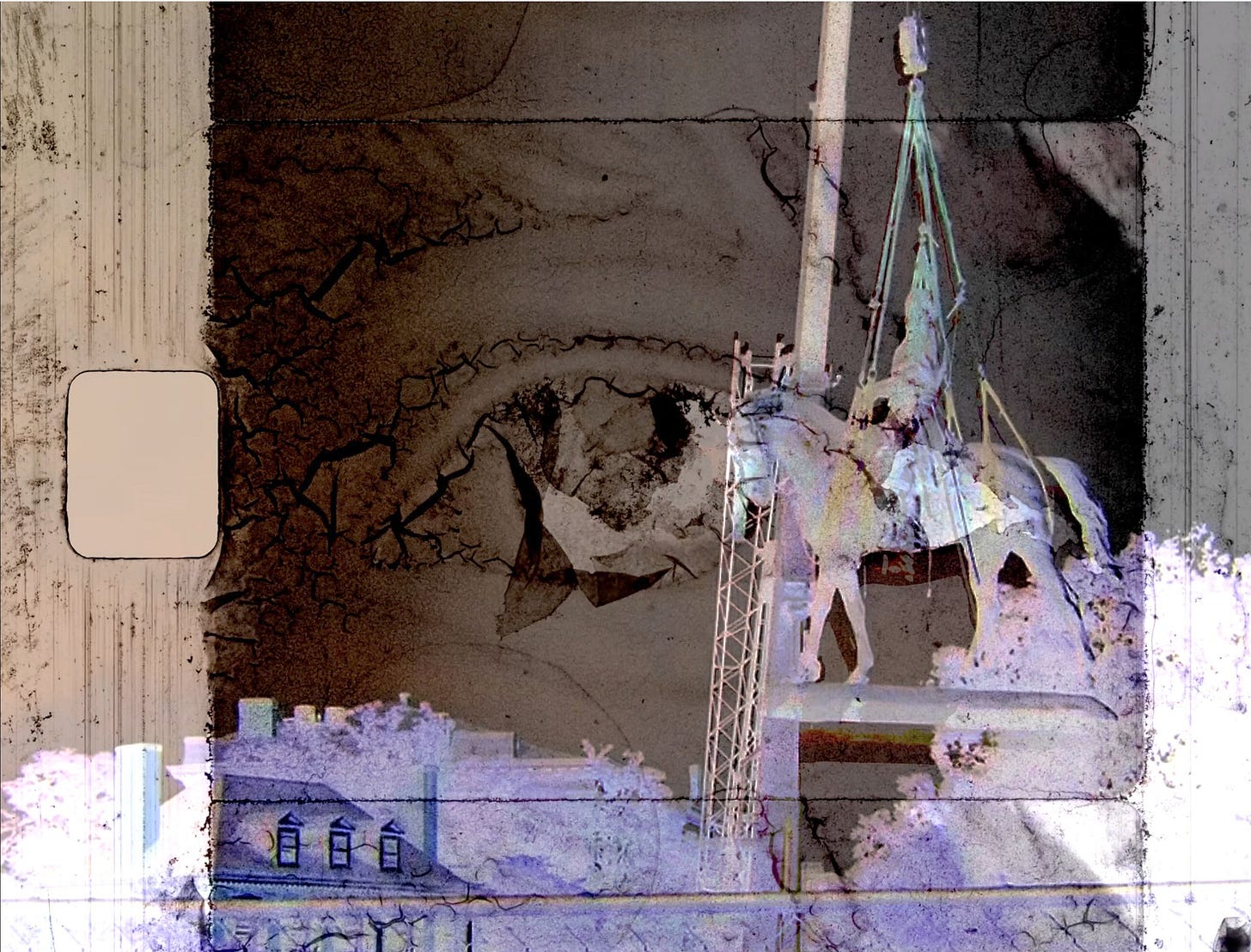

Very gradually, like light peering through clouds, layers of color emerge through the gray stone. These patches of saturated color emerge as video footage (also highly processed) of the protests and occupation of the former Lee Circle in Richmond, Virginia, which began in June 2020, and continued until the statue of General Robert E. Lee was finally removed on September 8, 2021. The first figures we see are the ominous, gas-mask covered faces of cops.

The pedestals of the statues, every square inch covered in political graffiti, are transformed by Drummond into colorful mosaics, pulsing with liquid vitality. We see protestors chanting, marching, lighting candles to memorialize those killed by police. Most strikingly, halfway through the film, we begin to see footage of dance performances at the protest site. These dances, performed by a troupe of black women, contrast vividly with the crumbling gray concrete of the dead presidents. Filled with energy and purpose, the women practice an art form which emanates from the impulses of the living human body, an art which depends on cooperation and collective action to come to fruition. The leftover monuments to the Lost Cause of Southern slave-ownership have been swamped and overtaken by the forces of life. Many colorful video layers are interwoven here, creating a sense of a diverse, multi-layered new life taking place in the center of Richmond.

Superimposed over the dancers, we see General Lee, his horse surrounded by a rope harness, ready for removal. Engineers in a nearby crane give the signal for the statue to be lifted. In a moment of cinematic magic, the group of dancing women have cast a powerful spell: powerful enough to cause a giant bronze horse and its rider to fly into the sky. The ever-watchful eye of George Washington, the slave-owning president, keeps vigil over Lee’s levitation, keenly concerned with the evolution of the Union.

In the film’s epilog, we see color footage taken from a moving car, showing the former Lee Circle as it stands today. The crowds are gone, but so are the monuments. Dusty trees and shrubs fill the center of the circle. The space feels empty, waiting, filled with potential. Its former persona has been roundly rejected, and the space waits, somewhat impatiently, for the people of Richmond to decide what kind of identity they want to forge for themselves in the future. The final image is of a white sprocket hole, over a black film frame, a space of potential, waiting for the light to burst through.

Drummond is posing a big question with his film: what are monuments? What are these gray, dour, stony faces, admonishing us from on high, which adorn our public places? Who are these dead white men on horses? And what secret power do they have, that a city full of people spend decades walking past them on a daily basis, never so much as glancing at them, and then, one day, everything turns on a dime, and surging crowds find themselves so enraged that they feel compelled to physically attack a bronze horse?

I spoke with two people I know, one in his 50s and one in his 80s, both black men who grew up in and around Richmond. Both spoke about how, before the protests, they never gave these statues of Confederate generals and presidents a thought. They walked past them without seeing them. But both described the protest movement as awakening them to feelings they had about the monuments, but hadn’t been aware of. Yes, it was galling to live in a city that celebrates these men who fought for the right to own human beings, but it took the pent-up frustrations borne of the pandemic and the lockdowns to bring these resentments out into the open. During the lockdowns, everyone lived under Jim Crow laws. In one sense, the Black Lives Matter movement came into being because it was forbidden to criticize the covid policies, and the accumulated resentment was re-channeled onto a safer target.

Traditional public monuments, like the statue of Jefferson Davis, are designed to feel so permanent, so eternal, that they resemble unchangeable laws of nature. Racism, capitalism, these are entrenched facts of social existence, and these monuments make them seem as permanent as the earth itself. The greatness of these dead men is literally carved in stone. Furthermore, they are designed to fade into the background, to be so permanent as to become invisible. If your goal is to make it impossible even to imagine the possibility of changing the racial power structure, what better way to express this impossibility then to make symbols which merge into the air we breathe, as we go about our daily business?

Then, one day, the unthinkable happens. The statues are covered with graffiti, and pulled from their pedestals. Suddenly, what yesterday was impossible to see becomes glaringly obvious to everyone: the sheer weirdness of the statues of Confederate generals. What does the city of Richmond think it’s doing, exhibiting these statues of slave-owners, traitors to our country, and warriors who lost their war? The fixation of the Lost Cause of the Confederacy is revealed as yet another symptom of deep trauma, inflicted on master and slave in different ways. Once you see this, you can’t un-see it; there’s no turning back.

Our current hyper-fixation on changing symbols and language at the expense of meaningful, effective social change is keeping us paralyzed. People open every meeting with a formulaic “acknowledgment” of being on native land, giving themselves permission to avoid taking any action that would be of benefit to any native person. The halls of power are not threatened in the least by attacks on statues. Yet, it’s inaccurate to say that symbols and language have no importance. The overwhelming emotion unleashed by the protests, the sense of suddenly being able to see a hidden truth, as expressed by the two men I spoke with, is a testament to the powerful effect which these statues had on the people of Richmond, and the rush of liberation and insight they felt when the seemingly unchangeable face of the city melted away.

In Drummond’s poetic, wordless visual essay, the crumbling and cracking of the filmstrip becomes miraculous, as the power of these authority figures collapses before our eyes. Among the rubble, a colorful liquid seeps in, with the fluid, ever-changing vitality of a community engaged in reclaiming public space. Music, dance, and visual art all erupt within this creative field, and even video art, as a protestor projects images of George Floyd onto the statue of General Lee. Drummond captures this transformative moment, this crack in the granite, this sudden efflorescence of change, and the complex, multi-layered textures of his visual language re-animate the strangeness and magic of the moment.

My articles on experimental film are freely available to all, but are supported by monthly and annual donations from readers. Please consider becoming a paid subscriber to support my work. Thank you.