The Kittens’ Tea Party, an 11 minute found footage film by MilleFeuille, begins with a sequence of clips from home security cameras, capturing footage of wild animals: coyotes, large cats, black bears, violating the boundaries of domestic space. At times, the boundaries they cross are literal fences which they jump over or try to bust through, and at times they are the symbolic boundaries of neatly clipped lawns and shrubs and well-swept porticos. Footage shot with night vision cameras turns the benign suburban landscape into an eerie, otherworldly spectacle: dark creatures prowling past ghostly white trees and shrubs. Lurid, blank white eyes stare out of dark, furry faces. These beasts come to us from the unknown depths of the wilderness and the equally unknown province of the night. We watch clips from uploaded home videos of domestic cats and dogs confronting bears and civets through windows, shrieking and striking out, in an attempt to frighten them off, which usually fails.

The film takes its title from an assortment of sentimental antique postcards which are interpolated into the security cam sequences, with fanciful illustrations of lovable kitties dressed up and participating in domestic delights. But when we watch a black bear taking a bath in a kids’ wading pool or breaking into a kitchen and rummaging through the fridge, there’s nothing cute about it. Last year a black bear came up to the window of my house and glanced at me with blasé indifference. Anyone who lives surrounded by wildlife, by animals attracted to the abundance of compost piles, vegetable gardens, and garbage containers, will feel disconcerted, watching these scenes. MilleFeuille’s editing adapts some of the tactics of horror films, such as cutting away from a scene just before a horrible moment of violence. These domestic horror scenes awaken us to our civilized discomfort with wildness.

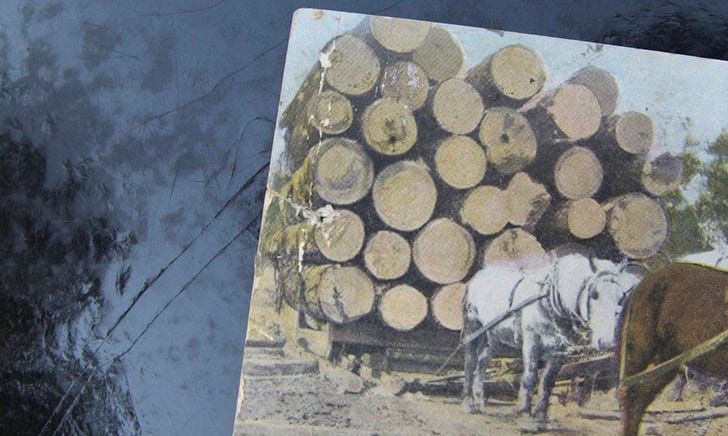

Postcards depicting nostalgic scenes of farm life, work animals yoked, harnessed, and comfortably put to man’s use, alternate with clips shot by worried homeowners as bears try to enter their homes. Not knowing what else to do, they resort to documenting their ordeal. The fact that so many people have uploaded security cam footage of these confrontations is a testament to our belief that documentation is tantamount to controlling, even surmounting, whatever is beyond our control. This dismay in the face of nature’s ruthlessness is augmented by clips of terrifying hurricanes and wildfires, shot from porches and through living room windows.

The Kittens’ Tea Party is a meditation on the current, uneasy moment in human civilization, in which we seem to be collectively testing how far we can go in conquering and controlling all wildness, while continually being devastated by nature’s refusal to be controlled. Mesmerized and comforted by technology, we turn to security cameras and phones for help. We can’t seem to stop or even slow down the floods, the fires, the invasions, but at least we can bear witness to our struggles, and broadcast them to the world, in a vain hope that these battles will not be forgotten. We’re a long way from the tame, comforting view of friendly domestic animals celebrated in the postcards, and even further away from the indigenous worldview of nature as teacher and partner.

A sense of ecological guilt hangs over many people, a consequence of the extreme degree to which mankind has neglected and damaged our mother, the earth. Our destruction of natural habitat is one of the main reasons wild animals venture into human communities. This guilt easily translates into fear, the fear that Mother Nature will strike back at us. (A fear which is extremely well-founded.) The Kittens’ Tea Party captures this guilt and this fear, by harnessing many individual examples of it and editing them together, skillfully structuring the whole so that it approaches a climax of unease and dismay. The postcard images, under an air-brushed haze of nostalgia and sentiment, function as a reference to an imaginary naive, civilized past, in which we viewed animals as cheerful playfellows and helpmeets. The postcards chide us. They point up our simple-minded wish that nature would simply go back to being cute and lovable, while deriding us for our naïveté, our refusal to face up to the consequences of our actions. MilleFeuille immerses us in this dilemma, challenging us to face it head-on.

My articles on experimental film are freely available to all, but are supported by monthly and annual donations from readers. Please consider becoming a paid subscriber to support my work. Thank you.