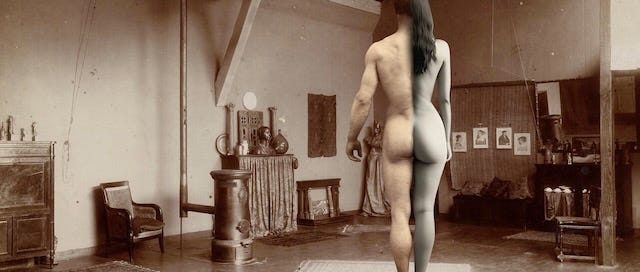

A slithery eel is the principle villain in Martin Gerigk’s 17 minute animated short Demi-Demons. The eel is a close cousin to the serpent in Genesis, but it also resembles a sperm cell, and it is frequently seen coiling around eggs. The film’s six sections are introduced with quotes from The Book of the Eel, a fictional scripture written to protect us from the eel’s evil influence. Gerigk’s stop-motion animation is created with photos, in sepia tones, some contributed by collage artist Nikola Gocić, setting the film’s prolog at the dawn of the industrial age. The opening scene looks like a bedroom with a cozy wood stove, but we also see a great deal of laboratory equipment: beakers, burners and microscopes. And indeed it is bedroom matters, specifically the cellular basis of sexual dimorphism, which are under investigation here. Sigils, symbols from medieval demonology, float over the lab equipment. The opening quote from The Book of the Eel: “Thou shalt not unlink the Sacred Codes.”

In the foreground stands a hybrid creature, literally half man/half woman (split vertically). This ambiguous hermaphrodite can be seen as a freak, a perversion of nature, or as a deep embodiment of human nature, encompassing its anima and animus, the alchemist’s ideal of the sexes fused, which Jung used as a symbol of the integrated, whole human being. This ambiguity proves to be a key to the film’s point of view.

The scientist working in the lab is the eel himself, who breathes a foul smoke onto a cell on a slide, causing it to divide into two dissimilar parts. The hermaphrodite splits into its male and female components. Sexual symbols appear superimposed on their bodies, a triangle for the male and an oval and fishtail for the female. The lab experiment has isolated and purified the cellular components of the two sexes, and these symbols now detach themselves from their owners and fly out the window, so they can be replicated and used for un-natural purposes. The Sacred Codes have been unlinked. A new morality is being articulated, and a new kind of sin: the sin of trying to hack inside the workings of the cell, and hijack the power of nature, using it for your own purposes. Mankind eats from the Tree of Knowledge, and falls from grace all over again; Eve divorces herself from Adam.

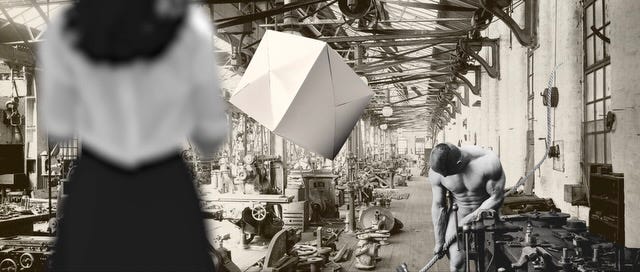

The “demi-demons” that float through the film, tempting people into biological sins, are depicted as geometric solids, such as icosahedrons. The suggestion is that it is mathematical abstraction itself, the ability to analyze living cells down to their coded structures, which poses the ultimate temptation, as it gives us power to rearrange nature and thus “play god,” which is the ultimate hubris and folly.

In the second section, the Eve figure sets off on her own, taking a trip to a factory. We hear from The Book of the Eel that she is “seeking new manners of enticement.” Once again, the implication is that the temptation of sin is the temptation to “get inside the machinery” of life and mess around with it. This enticement is made explicitly sexual when a naked, muscle-bound hunk is seen handling a forge, also an allusion to the marriage of Aphrodite and Hephaestus. Her eyes light up; her lips open. We hear sighs of pleasure. She seems to be turned on by the machinery, the flames, the chemical symbols. Scientific knowledge seems to promise us unlimited power to re-design the world to our own liking. But the power also contains the threat of unleashing catastrophe into the world on a massive scale.

If altering the machinery of biology is a sin, then the film proposes a more nature-centered ethical system. The Christian virtue of obedience to God is re-cast as obedience to the power and wisdom of nature, which evolves balanced ecosystems over tens of thousands of years. Because process of evolution consists of such a vast number of incremental changes, the “wisdom” of nature is just about infinitely smarter than human intelligence. The human intellect has a truly astonishing ability to over-value itself, for people to think that they know better than nature itself. Nothing could be more absurd than this.

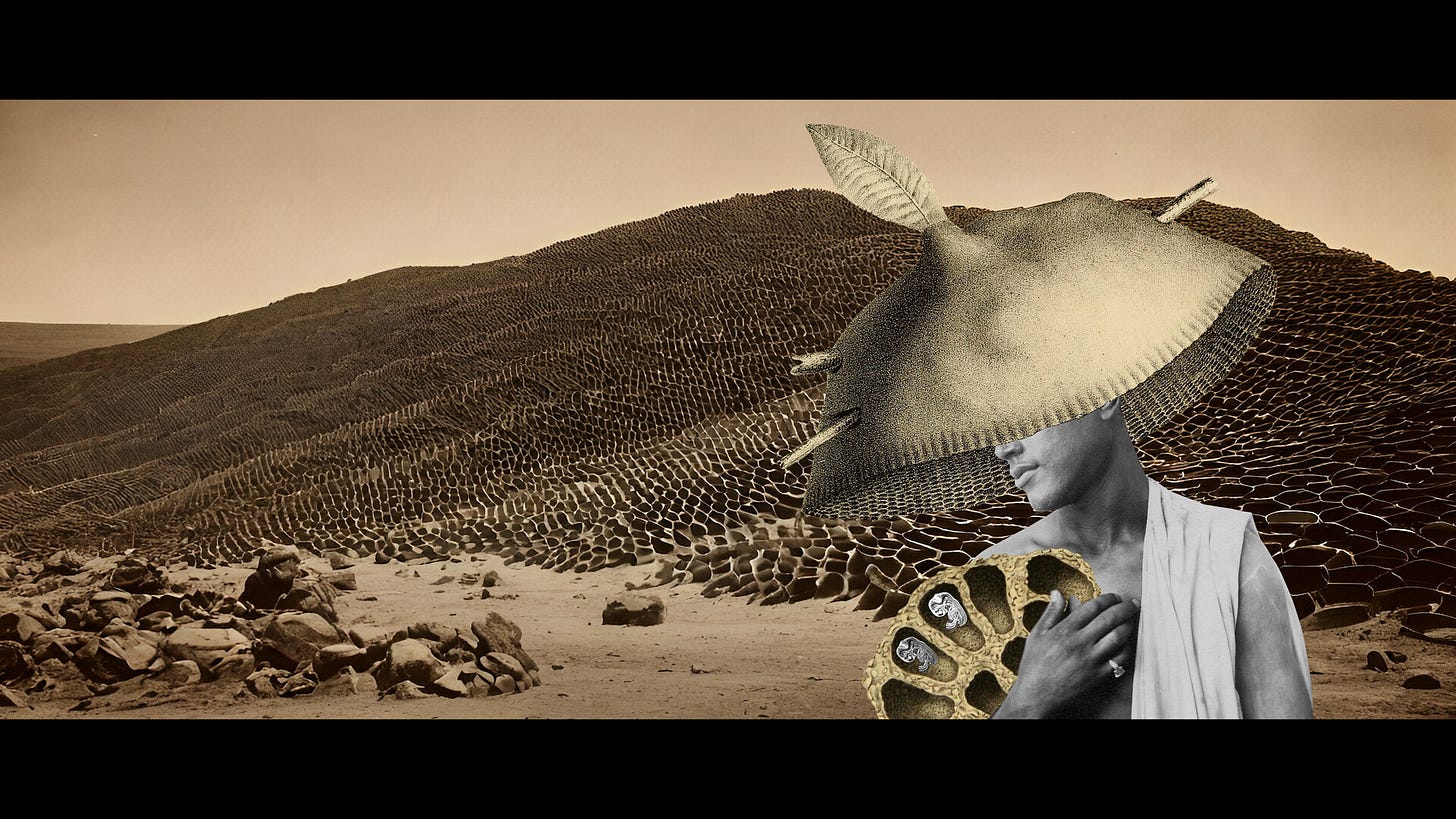

The third section deals with manipulating consciousness through chemicals, in a series of strikingly psychedelic landscapes, with the man and woman merging with plants and mushrooms. As with all the “sins” delineated in this film, this one is full of ambiguity. On the one hand, it suggests that using laboratory chemicals, such as MDMA, to change your consciousness, is wrong, because it disrupts and distorts the brain’s natural functioning. The shortcut of using chemicals to induce visions deprives a person of the inner knowledge and control they might have gained, if they achieved the same transcendence through the techniques of meditation.

But the use of sacred plants for spiritual knowledge and transcendence is an ancient practice which is considered sacred, rather than sinful. The fact that these plants grow in our immediate environment, and contain chemical keys which cleanse the “doors of perception” as William Blake put it (via Huxley), suggests that humans co-evolved with these plants for a purpose, that we are meant to use these plants to gain higher knowledge. This can also be seen as another version of the Tree of Knowledge in Genesis, where the apple is really a mushroom or peyote cactus.

A section called “Intermezzo” is set in an environment of digital displays, covered in binary code, the online world in which most people are now immersed. Two bearded naked men are checking each other out with a great deal of curiosity, while being caressed by an eel-like pipe. Meanwhile, a woman with eel-arms and wearing high-heeled boots is cracking her arms like a whip, evidently a dominatrix. Everyone stares at the screens, fixated. The focus shifts to more familiar forms of “temptation” and “sin,” but explicitly linking sex to computers. After all, what do people use their devices for, a great deal of the time? Porn and hooking up. One could describe this version of sexual “sin” as the sin of directing the wonderful erotic power which nature gives to us towards fantasy images, rather than towards a human being, as nature intends. An image of a solar eclipse underlines this sense of the life-force becoming blocked.

We see a glass beaker being drained of fluid, and an ocean being depleted, leaving a lifeless desert. Ecological disaster, certainly, can follow from tampering with nature. But internally, the “juiciness” of life, all the joy and meaningfulness of being alive, healthy, well-nourished, erotically fulfilled, can drain out of life as we replace our natural needs and drives with artificial substitutes. We’re left feeling empty.

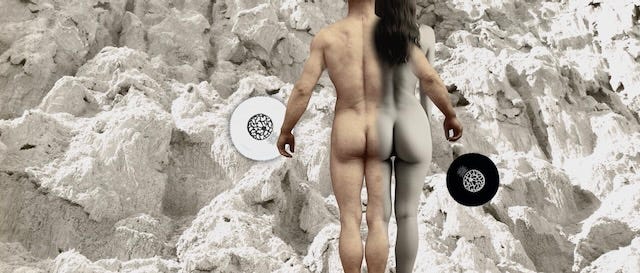

The final section examines laboratory interventions in human reproduction, such as in vitro fertilization, again using a suggestively poetic visual language. In the nature-aligned ethics of the film, these technologies undermine the infinite wisdom of evolution in choosing when and how to propagate the species.

So who are these demons, tempting us to become addicted to online porn, artificially induce hallucinations, remodel our external genitalia to taste, and choose when and how to become parents? The logic of “following the money” will lead us directly to the purveyors of porn, the manufacturers of addictive designer drugs, and companies that sell “gender affirmation” surgery and fertility services. The demons, it seems, are all capitalists. Laissez-faire capitalism was originally justified by a perverse understanding of Darwin’s theory of “survival of the fittest,” but private property is unknown among animals. A bird may fight to defend its nest, but the bird isn’t going to “buy” a thousand other nests and start charging the other birds rent.

In nature’s complex ethics, individual organisms behave and evolve to their own advantage: devouring others, sometimes deceiving them, but sometimes cooperating symbiotically. On the level of entire ecosystems, the push is towards dynamic balance and the sustained homeostasis of a “climax” community. This tension, between the drive of each individual and each species to survive, and the tendency of the system to achieve overall balance, is essential: it’s the engine that drives evolution forward.

The film’s demons are urging individuals to “sin” against the structure of the system, and manipulate it to perceived personal advantage (which usually turns out to be a personal disadvantage). Which system of ethics should prevail? The desire of an individual woman to be a mother, although she can’t conceive naturally? The drive of corporations to devastate an ecosystem for quick profit? Nature’s drive towards slowly repairing mankind’s messes? Gerigk’s vision includes the full complexity and nuance of these ethics, of trying to decide in which circumstances a biological sin might be “good” or “bad.”

In the film’s epilog, we see a kind of catastrophic mirror image of the prolog. Ecological disaster has occurred: the oceans are gone, and the world is a lifeless desert. The man and woman have become empty, dry, lifeless. They are reunited in their hybrid body, but this union now seems monstrous, denying the sexed, dimorphic reality of human life. Such are the wages of sin.

We fight endless battles with ourselves, with one another, with nature. But nature cares nothing about our personal desires and our economic schemes. It’s a limited world, with limited resources, and in the end, it will re-balance itself, whether we like it or not. As filmmaker Antero Alli pointed out, our notion that the planet needs us to “save” it is absurd. A more useful focus would be on what we need, in order to provide a sustainable, peaceful world for us all to enjoy living in. The answer lies in observing nature, in her micro-structures as well as her macro-structures, and learning how to work with her, rather than against her. The temptation of the demonic eels is the temptation to ignore nature’s voice, and succumb to false promises of power and pleasure. These temptations won’t help us or help the planet, but they’ll certainly generate a lot of cash for the eels.

My articles on experimental film are freely available to all, but are supported by monthly and annual donations from readers. Please consider becoming a paid subscriber to support my work. Thank you.