In Martin Gerigk’s six minute animated short Demi-Gods, the first demi-god we see is a fantastic chimera, a conglomeration of flowers, frogs and seed pods, bound to a muscular male human torso. Hovering over a railway junction, he releases a menacing-looking cloud of vapor, which seems to throw the track switch, making the train change directions. Sirens begin sounding, cannons begin firing, a war has been launched. This particular demi-god seems to get his jollies by unleashing strife and conflict. The hovering, mystical figure is a Chaos Agent par excellence.

This film, like Gerigk’s companion film Demi-Goddesses, is a collaboration with Nikola Gocić, who supplies the antique photos and illustrations which Gerigk uses in his animations. In this film, with its sparse landscapes populated by hybrid and fantastical creatures, these vintage materials are used to strikingly surreal effect. The resulting visual style is reminiscent of Max Ernst’s collages, which he made from 19th century engravings.

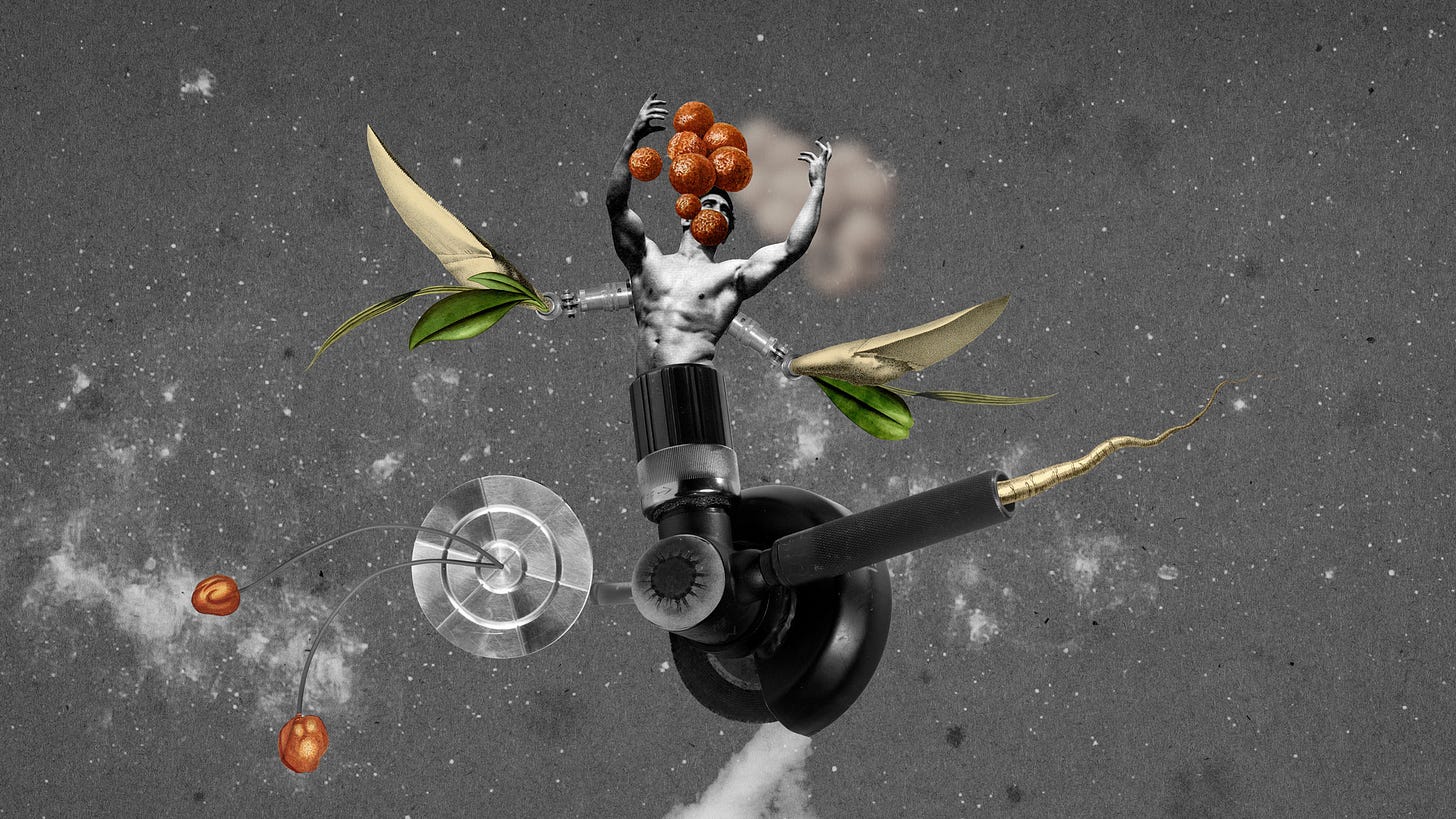

A section entitled La Sensualité du Narcissme features another heroically muscular god floating through the night sky, propelled slowly along by some kind of combustion engine, his complex mechanical apparatus emitting roots, leaves and seeds. We hear occasional female sighs of pleasure, stylized into musical phrases, calling to mind the “sensualité” of the title. These sensual sighs pair strangely with this enigmatic figure, releasing seeds from his tubes and sprouting leaves at key intervals. It is almost as if we are inside the hormonal system, observing one of the hormonal demi-gods who control our emotions and responses, as he releases precisely-timed chemical signals, triggering our experience of pleasure and attraction. And what of the “narcissism” of the title? Perhaps it suggests a perverse inner mechanism, a neurotic disconnection from external reality, when a person loses his desire to make meaningful connections to other people, and becomes addicted to the chemical pleasure-reward of sensation as his only goal. The heavy, awkward quality of these hybrid creatures, joining together creaky machinery with organic elements, suggests this kind of perversion, an artificial amplification of certain behaviors, a mechanistic means of repeatedly receiving a biochemical high. It’s a visualization of addiction itself.

The final section, Genetic Hubris, can be seen as inspired by the technique of gene splicing. A girl fairy hovers over a flower, a distinctly fleshy-looking flower with orifices, emphasizing its sexual nature. One of the floating demi-gods, a peculiar pirate figure, with a spike peg leg and a pair of wire cutters for a hand, cuts the genetic strand emitted by the flower, quickly causing its resident fairy to vanish, and the flower to die. In his other hand he holds a seedling as a kind of battle standard, proclaiming and upholding his right to promote his preferred version of the species. It is indeed an act of hubris for the human mind to imagine that it can design an organism that improves on nature. This hubristic error generally results in death. It’s not nice to try to fool Mother Nature.

If the notion of demi-gods or goddesses brings to mind the common human perception that our lives are being guided and influenced by unseen forces, Gerigk’s metaphorical references to the artificial manipulation of DNA or hormones is an interesting one. Mythical references to gods and goddesses can be seen as an expression of the universal human experience of being subject to one’s own biochemistry: powerful systems within us that function with their own agendas and preferences, operating beneath our conscious awareness. Our attempt to “game” these bio-systems chemically is an attempt to “play god,” to claim a semi-divine status. On the other hand, the demi-god of the opening section, who instigates war, reminds us that our social structures, too, are clearly being manipulated by powerful forces, hidden behind a curtain. These would-be world-makers likely imagine themselves as semi-divine as well, shapers of history.

As is usual with Gerigk, his music subtly underlines and colors the key moments and actions throughout the film. All the film’s elements work together: color, texture, musical timbre, rhythm. They harmonize perfectly to create these miniature portraits of perversity, the artificial joining of the mechanical with the biological. Their odd synthesis creates its own, peculiar kind of uncanny, fascinating beauty.

My articles on experimental film are freely available to all, but are supported by monthly and annual donations from readers. Please consider becoming a paid subscriber to support my work. Thank you.